In early October, the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC 82) set a clear pathway for future black carbon regulation, when the committee agreed that the concept of “polar fuels” would be further considered at a technical committee meeting in January 2025 (PPR 12).

This new course must see the IMO and its Member States rapidly developing mandatory regulations to radically reduce black carbon emissions – and these new rules must be prepared in a matter of months, so that they can be approved at MEPC 83 in April 2025 and adopted by 2026.

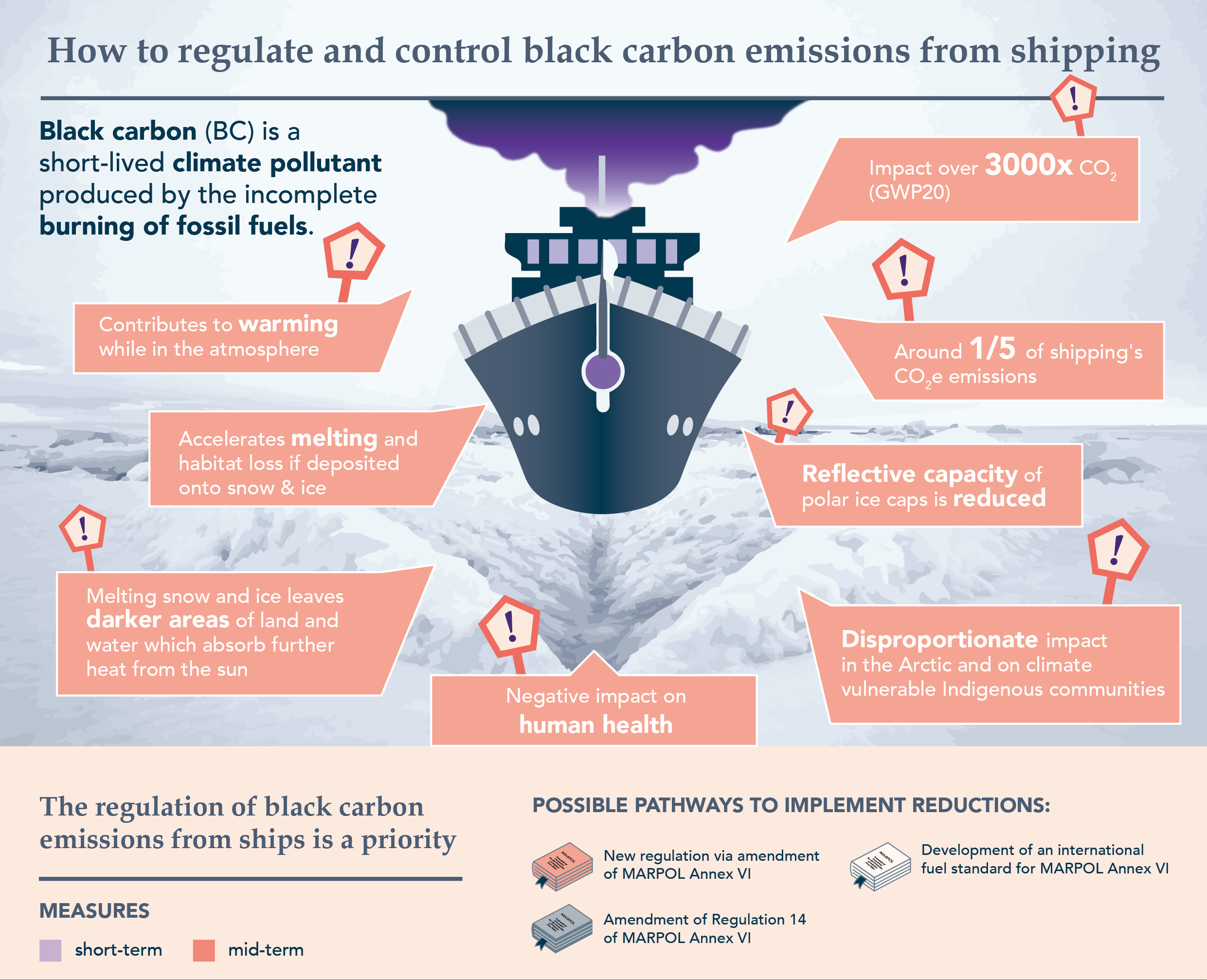

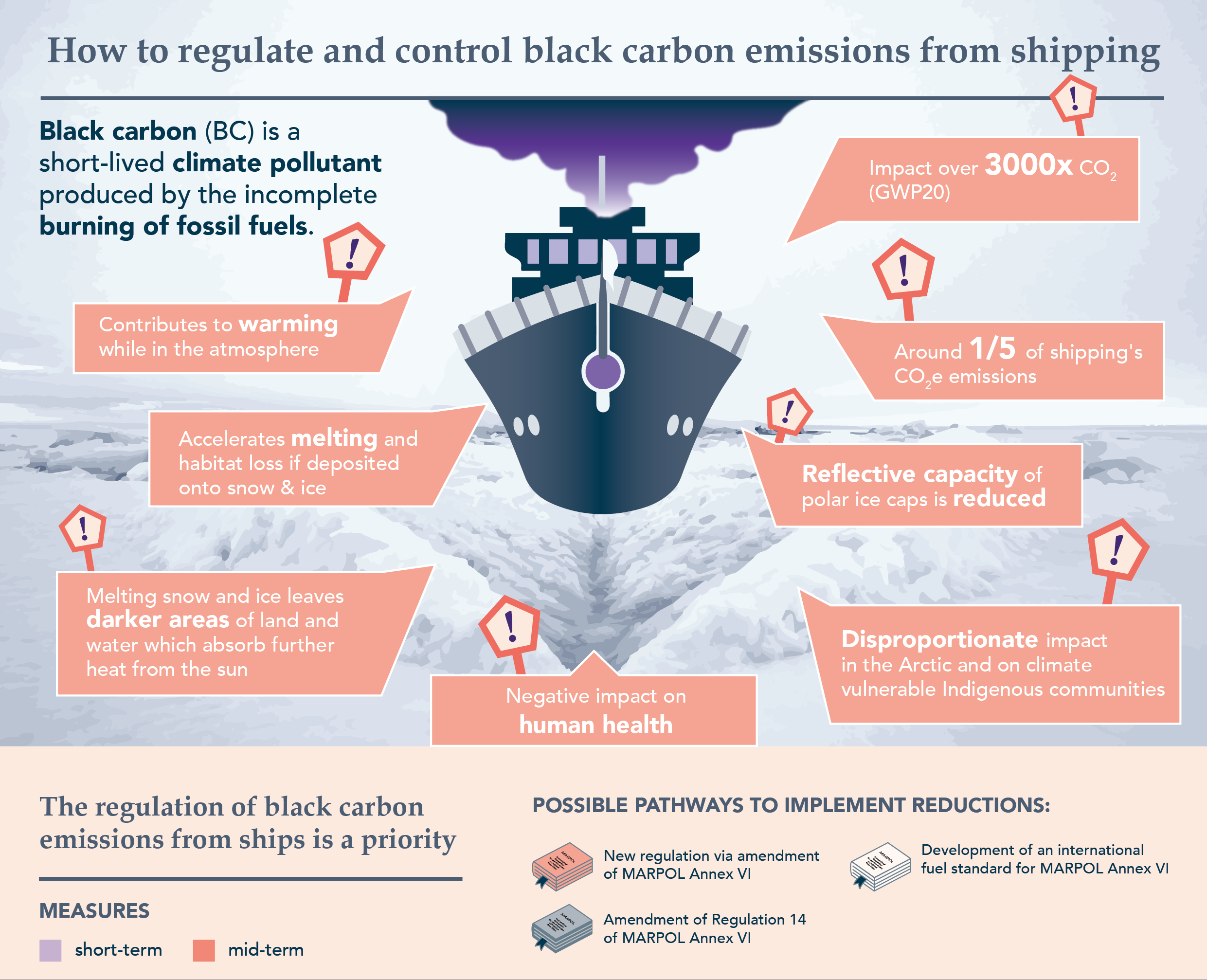

Following a decade of procrastination, progress is certainly to be welcomed – after all, IMO has been discussing the Arctic impact of black carbon from ships since 2011. It has long been recognised that ships can reduce their black carbon emissions in a variety of ways, but without rules in place, emissions are increasing globally – and have more than doubled in the Arctic. Black carbon is a short-lived climate pollutant, produced by the incomplete burning of fossil fuels, with an impact more than three thousand times that of CO2 over a 20-year period. It makes up around one-fifth of international shipping’s climate impact – which contributes around 3% of all human sources of climate-warming greenhouse gases. Not only does it contribute to warming while in the atmosphere, black carbon accelerates melting when it falls onto snow and ice.

This melting exposes darker areas of land and water which then absorb further heat from the sun, while the reflective capacity of the planet’s polar ice caps is severely reduced. More heat in the polar systems results in increased melting. This is the loss of the albedo effect – scientists recently announced that the Arctic’s reflectivity has weakened by 24% since 1980.

Declines in sea ice extent and volume are leading to a burgeoning social and environmental crisis in the Arctic, while cascading changes are impacting global climate and ocean circulation. Scientists have high confidence that processes are nearing points beyond which rapid and irreversible changes on the scale of multiple human generations are possible.

By using cleaner fuels for ships, black carbon emissions can be reduced – typically by switching ships from using dirty residual fuels – like heavy fuel oil – to lighter distillates. This alone could reduce black carbon emissions by between 50 and 80%, depending on the type of engine, while installing technology such as diesel particulate filters would remove further black carbon from ships’ exhausts, much like cars today.

IMO Member States have now been tasked with providing comments and proposals on the concept of polar fuels, taking into account the Clean Arctic Alliance’s members’ submission to MEPC 82, which seeks to set out the fuel characteristics that would distinguish polar fuels from residual fuels, and thus lead to fuel-based reductions in black carbon emissions from ships. Some countries have suggested that any outcome on polar fuels could be first included in existing best practice guidance, however a number of Arctic countries supported the idea of mandatory regulation.

However, it would be irresponsible and reckless for the IMO to further delay the shipping sector’s response to the significant threat to the Arctic and to Arctic tipping points (tipping points are changes that once they have occurred are virtually impossible to reverse) posed by black carbon emissions. The Arctic is in crisis, in fact – the whole planet is in crisis. To continue to allow unregulated emissions of a short-lived climate forcing pollutant in the Arctic is quite simply negligent, and will have unprecedented repercussions for the planet and humanity globally. There is little time left if the IMO is to have any impact on slowing down the loss of Arctic sea ice or the melt of the Greenland ice sheet.

It will be important however that a move from dirty heavy fuels to lighter diesel fuels does not prevent the flourishing of other cleaner new fuels, or other forms of propulsion, including wind power. So, the black carbon regulation must be written in such a way that it eliminates the use of the dirtiest fuels and requires ships operating in or near to the Arctic to move to cleaner alternative fuels – polar fuels – including distillate fuels, but also allowing the use of “new” low or zero carbon, non-fossil fuels or other forms of propulsion that are now becoming commercially available.

So, the clock is ticking – the IMO and its Member States have just a few months to develop these mandatory regulations, which must be effective in radically reducing black carbon emissions – and these new rules can be, and must be approved at MEPC 83 in April 2025 and adopted by 2026.

See our 2023 infographic, How to regulate and control black carbon emissions from shipping

Other issues: Emission Control Areas at MEPC 82

During MEPC 82, two new emission control areas (ECA) were adopted and will come into effect from 1 March 2026, covering the Canadian Arctic waters and the Norwegian Sea. While ECAs, which are sea areas with stricter rules, are designed to require ships to reduce nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulphur oxides (SOx) and particulate matter (PM) emissions, because they enforce the use of cleaner fuels by ships they also have a co-benefit of reducing black carbon emissions.

At MEPC 82, the Committee also heard a presentation led by the government of Portugal setting out the background studies for a further ECA in the north Atlantic. The boundaries of this future ECA have not yet been decided but could potentially stretch from Portuguese waters to the coast of Greenland, reducing NOx, SOx and PM, with consequent improvements in air quality and the health of coastal communities along the European western seaboard.

Creation of this ECA would again ensure that black carbon emissions would be reduced which is further good news for the Arctic. When ships sail north of 60 degrees, their impact from black carbon emissions is the greatest. However, as black carbon remains in the atmosphere for a few days or weeks, dependent on prevailing winds, it can be transported to the Arctic from further south. So measures to reduce black carbon emissions from ships sailing north of 40 degrees North – just north of the Mediterranean Sea – will be immensely beneficial in terms of reducing the impact of shipping’s black carbon emissions on the Arctic.

While this is all very welcome news, it does not negate the need for an Arctic-wide black carbon regulation. Although the new ECAs and a future Atlantic ECA will improve air quality and the health of coastal populations, the fact is until the IMO puts in place mandatory regulations, emissions of black carbon – a potent short-lived climate forcer – from ships remain totally unregulated.

What else happened at MEPC 82?

In respect to addressing the impact of underwater noise from shipping, there was good progress at MEPC 82 with the proposed Action Plan supporting new underwater noise guidelines being agreed and an experience building phase (EBP) based on the revised IMO guidelines adopted last year on track to build knowledge and set the foundation for potential mandatory measures in the future.

Not all issues made such good progress. It is essential that IMO member states embrace ambitious climate action and properly resource and pick up the pace of negotiations if the IMO is to ensure that shipping’s climate pollution peaks and reduces in line with its 2023 GHG strategy, thus curbing the sector’s contribution to the worst impacts of climate breakdown and the Arctic climate crisis.

This means reaching agreement on all three technical measures currently under consideration – revision of the IMO’s carbon intensity indicator, adoption of a strong global fuel standard and an ambitious carbon levy. The Clean Arctic Alliance is concerned at the lack of urgency around the strengthening the IMO’s energy efficiency measure – the carbon intensity indicator (or CII). Failure to maximise the efficiency of the shipping sector immediately through a strengthened CII seriously threatens the IMO’s goal of cutting shipping emissions by 30% by 2030.

Frustratingly, there was no progress at MEPC 82 on the issue of using exhaust gas cleaning systems, or scrubbers, to circumvent the IMO’s global requirement to use cleaner, low-sulphur fuels. Another emission from ships currently unregulated is the discharge of the wastewater produced by scrubbers which thousands of ships have installed so that they can continue to use the dirtiest, high-sulphur fuels (banned for use on land many years ago because of the acid rain and health impacts).

Scientists have recently announced that humanity has passed the planetary boundary for ocean acidification, with the Arctic ocean acidifying faster than the global ocean, yet scrubber wastewater which is acidic can be dumped into the ocean anywhere – even in marine protected areas and critical marine wildlife habitats. Any further consideration of the use of scrubbers by ships and the discharge of scrubber wastewater was postponed to next year and as a consequence over 5000 ships will continue to pump gigatons of acidic and toxic scrubber wastewater into the ocean, instead of protecting important wildlife habitats and protected areas and banning the use of scrubbers in the Arctic.

Another issue which also has an impact on the ocean’s ability to act as a carbon sink – discharge of marine plastic litter – was also deflected to the next meeting of the body Pollution Prevention and Response (PPR) sub-committee.

Finally, MEPC 82 also welcomed the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). The GBF is a landmark agreement that was adopted in December 2022 to reverse biodiversity loss. The Clean Arctic Alliance is proposing a high level task force be created which would elevate the global threats of biodiversity loss and marine pollution to the same level of urgency as climate heating. The task force would be charged with creating a co-benefits action plan to make urgent progress on addressing shipping’s contribution to the triple planetary crisis. On the need for MEPC to respond adequately to the triple planetary crisis – pollution, biodiversity and climate, and to ensure that action is taken which contributes to the avoidance of planetary climate tipping points and global shipping operating within planetary boundaries, there is a clear need to keep educating the Committee.

Dr Sian Prior is Lead Advisor to the Clean Arctic Alliance; Dave Walsh is the Alliance’s Communications Advisor