In January 2025, during a meeting of the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) Pollution Prevention and Response sub-committee (PPR 12), a growing number of IMO member states, along with parts of the fuel and shipping industry, demonstrated broad support for development of the “polar fuels” concept to help define fuels for use by Arctic shipping. “Polar fuels” would be cleaner and have lower emissions of black carbon – deemed a “super pollutant” for its outsize impact on both human health and the climate.

Despite this progress, shipping nations urgently need to get a move on, as they have yet to provide any commitment on how to effectively regulate emissions of black carbon through the use of these fuels or a timeframe for regulation and black carbon emissions from ships remain completely unregulated.

Time is key. Governments – and thus IMO member states – cannot be complacent, or continue to put off decision-making. The Arctic has already experienced a massive loss of ice volume – retreating sea ice and melting ice sheets – leading to the loss of critical ice habitats and to increasing sea level rise. On March 26, the US National Snow and Ice Data Center announced that Arctic sea ice had set a record low maximum. In 47 years of satellite data, never before has sea ice covered so little of the Arctic in winter. The Antarctic too – according to the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, global sea ice cover reached a record low in February this year. The polar regions are the greatest regulators of our global climate – the Arctic climate crisis is happening now, and it is having repercussions everywhere on Earth.

Rules on black carbon are coming – it’s one of the longest, unresolved issues running at the IMO, and must be dealt with without delay (visit our webpage: How the IMO Came to Work on Black Carbon?).

Other sectors have been taking active steps to reduce black carbon emissions for a decade. Now IMO member states must urgently commit to the development and adoption of the best possible regulation for inclusion in MARPOL Annex VI – the international convention which regulates discharges and emissions from ships – ahead of their next meeting – PPR 13 in early 2026. This new mandatory rule should introduce a requirement that only polar fuels – once defined – should be used by ships operating in and near to the Arctic.

2026! That’s a long time away. What happens in the meantime?

A year will pass quickly, so action is needed now to get everything in place. To ensure all shipping in the Arctic will follow the same rules, IMO member states, led by Arctic countries like Norway, Iceland, Canada, Denmark, Greenland, Sweden and Finland, and supported by climate-vulnerable countries and the shipping and fuel industry, must agree on concrete plans for regulation by summer 2025, to effectively prevent the use of heavy residual fuels in the Arctic. If they achieve this, then outreach and consultation can take place in the early autumn.

In addition, the Arctic Council – comprising all eight Arctic countries as well as Arctic Indigenous Permanent Participants – is expected to step up its existing black carbon reduction commitments at a Norway-led Ministerial meeting this May. Their existing target to reduce Arctic black carbon emissions across all sectors by 25 – 33% over 2013 levels is on course to be met this year. Setting a more ambitious post 2025 reduction target will bring added pressure on IMO member states to act on shipping.

What’s the connection between black carbon, the Arctic and the shipping industry?

The Arctic is warming four times faster than the rest of the planet, and rapidly approaching the point where such as the loss of sea ice and melting of the Greenland ice sheet, are affecting ocean circulation patterns in the North Atlantic.

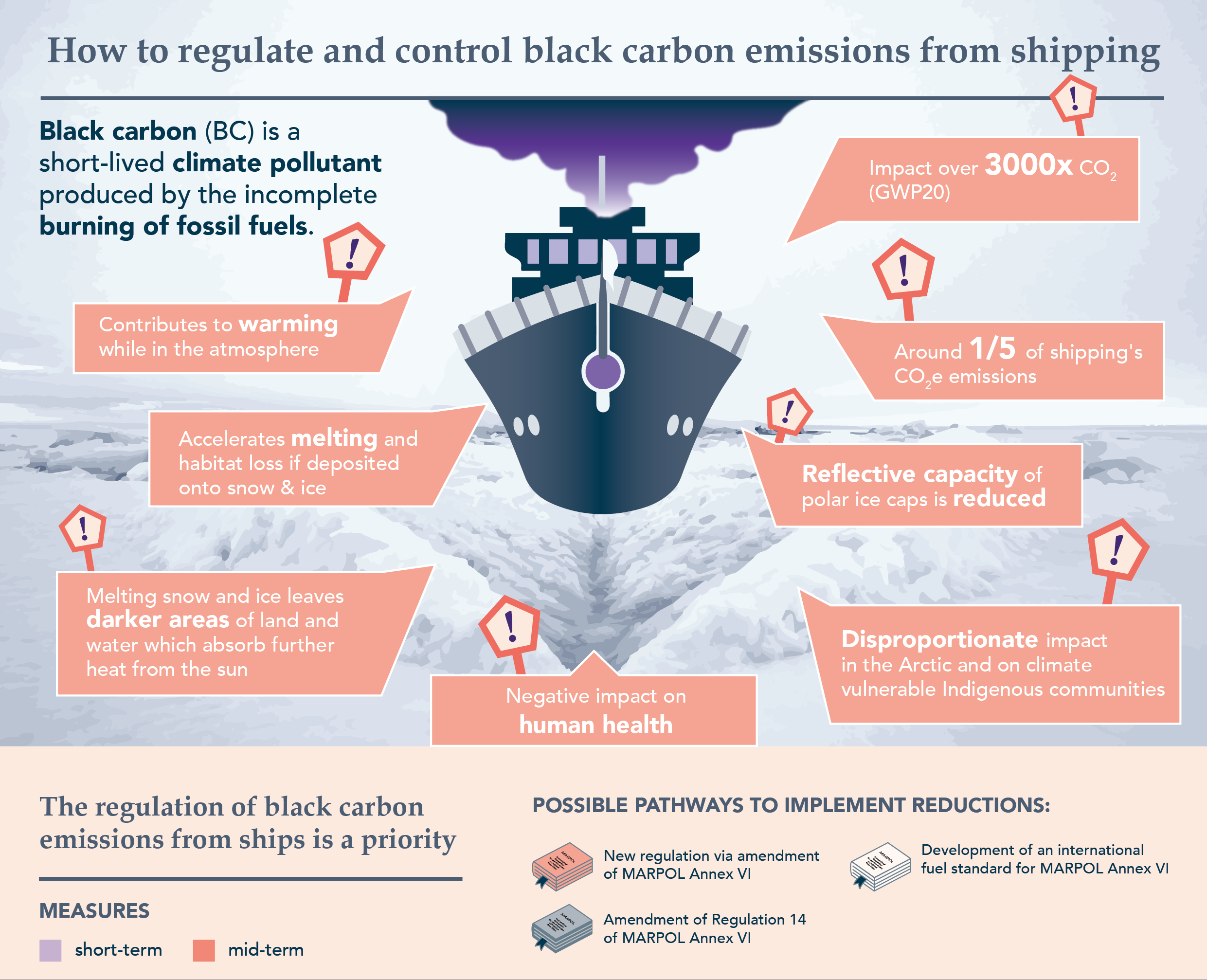

Black carbon is solid particulate matter – which we call soot – produced by the incomplete burning of fossil fuels in the engine combustion chambers and then ejected into the atmosphere. This soot absorbs sunlight and by warming the surrounding atmosphere becomes a powerful short-lived climate pollutant, aka super pollutant. Although black carbon is not a greenhouse gas, these emissions form “shipping’s second largest cause of global warming” after carbon dioxide, and makes up around one-fifth of international shipping’s already considerable climate impact.

Overall, black carbon contributes more than three thousand times the climate warming impact of the same mass of CO2 in the atmosphere over a 20 year period. In its recent 6th Assessment Report, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) doubled the estimate of the warming potential of black carbon on snow and ice compared with the 5th Assessment Report due to a better understanding of its impact on snow forcing.

After they are emitted from ship exhausts, black carbon particles are suspended in the atmosphere, where they absorb heat from the sun. When the particles fall to earth – or in this case, the Arctic, this black soot falls onto white ice or snow, where it lowers the reflectivity – or albedo, causing a detrimental absorption of more heat and thus accelerates melting. The feedback loop continues when the snow or ice melts, exposing darker areas of land and water which absorb further heat from the sun, thus reducing the reflective capacity of the planet’s polar ice cap.

More heat in the polar systems equals increased melting. While this seems obvious, scientists are seeing ever more clearly the alarming consequences.. Declines in sea ice extent and volume are leading to a burgeoning social and environmental crisis in the Arctic, while cascading changes are impacting global climate and ocean circulation. Scientists have high confidence that processes are nearing points beyond which rapid and irreversible changes with serious implications for humanity, and research shows within the next decade we will start to see periods when no Arctic summer sea ice is formed, and that “preparations need to be made for the increased extreme weather across the northern hemisphere that is likely to occur as a result.”

How Many Ships Go to the Arctic? Can They Really Do So Much Damage?

A consequence of the reduced extent of Arctic sea ice is increased access to oil and gas and mineral resources in the Arctic, resulting in increased shipping to service this exploration and export the products. In the past decade, the number of individual ships has increased by around 40% and the distances being sailed in the Arctic increased by over 100%. Inevitably this means that atmospheric emissions have also increased with black carbon emissions more than doubling.

What are Polar Fuels?

Polar fuels are cleaner marine fuels, appropriate for use in the Arctic that will lower emissions of ship black carbon. During PPR 12 at the IMO in January 2025, the marine fuel industry identified and demonstrated the characteristics which could be used to define” polar fuels” in an IMO regulation. Distillate grade fuels and low or zero emission fuels would replace residual fuels (like low sulphur heavy fuel oil) in the Arctic and lower ship black carbon emissions. While still fossil fuels, distillate grade fuels are both readily and widely available globally, far easier to clean up if spilt than residual fuel and could form the basis of a new mandatory IMO regulation. This is a significant step in the transition to low or zero emission fuels being developed to reduce ship greenhouse gas emissions, and could finally lead to real cuts in shipping’s climate impacts on the Arctic.

Does black carbon have other impacts?

For most of us, even those of us who live near ports, the shipping industry is, at best, out of sight out of mind. However, the global shipping industry makes up around 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions – comparable to an entire country, like Germany or Japan, and creates air pollution – via particulate matter in the form of black carbon, that threatens the lives of people living in or around ports, and contributes to heating the Arctic region.

In March 2025, health experts, speaking at the World Health Organization’s Air Pollution Conference in Colombia, argued that black carbon along with methane and ozone are responsible for nearly half of global temperature increases to date and reducing emissions of ‘super pollutants’ would slam emergency brake on global warming.

As well as heating the planet, black carbon emissions from ships also have a direct negative impact on human health – ultra fine soot particles are inhaled and make their way deep into the lungs and the bloodstream, resulting in cardiovascular and respiratory disease and premature death.Recent research even has found black carbon particles in the body tissues of foetuses, following inhalation by pregnant mothers.

The need to reduce emissions of black carbon because of both the climate and health impacts has been long recognised. On land, considerable effort has been made to ban dirtier fuels in power stations, to install diesel particulate filters on land-based transport, and to improve the burning of dry wood – all to reduce emissions of black carbon and improve air quality..However, at sea the same efforts have not yet been made – something that IMO member states must urgently rectify.

We recommend taking a look at the latest report from the Clean Air Fund: Tackling Black Carbon: How to Unlock Fast Climate and Clean Air Benefits, which recommends cutting black carbon from shipping “as quickly as possible”.

“The case for action on black carbon is clear… decision-makers can cut emissions to unlock near-immediate climate gains, while improving air quality, public health and economies.”

So, to roundup – what needs to happen in the coming year to cut shipping’s black carbon problem?

Arctic countries, along with countries that are vulnerable to the impacts of the loss of Arctic sea ice and melting of the Greenland ice cap such as low-lying island nations, must urgently collaborate and propose a strong mandatory measure to reduce emissions of black carbon from ships for consideration by PPR 13 in early 2026. The Clean Arctic Alliance believes that the simplest approach would be to agree and adopt a regulation which requires that Arctic shipping can only use cleaner fuels which result in lower black carbon emissions when operating in the Arctic.

Dr Sian Prior is the Lead Advisor to the Clean Arctic Alliance