First published on Climate Home news, March 18, 2021

Climate change is having a more rapid impact in the Arctic than anywhere else right now – the recent cold weather that blanketed North America and Europe, and caused chaos in places like Texas, has been linked to the consequences of a warming Arctic. What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic – changes taking place in the north will have repercussions further south.

While there is widespread awareness of how greenhouse gas emissions drive global climate warming, what is less well known is how emissions of black carbon particles from forest fires, wood stoves, flaring, energy generation – and transport, including shipping, contribute to Arctic warming.

Although shipping contributes just 2% of the black carbon emitted in the Arctic, it has a much greater heating impact. When emitted by ships in and near the Arctic, black carbon particles enter the lower levels of the atmosphere, where they remain for under two weeks, absorbing heat. But it eventually comes to land on snow or ice, black carbon’s warming impact is 7 to 10 times greater, as it reduces the reflectivity (albedo) and continues to absorb heat, accelerating the Arctic melt.

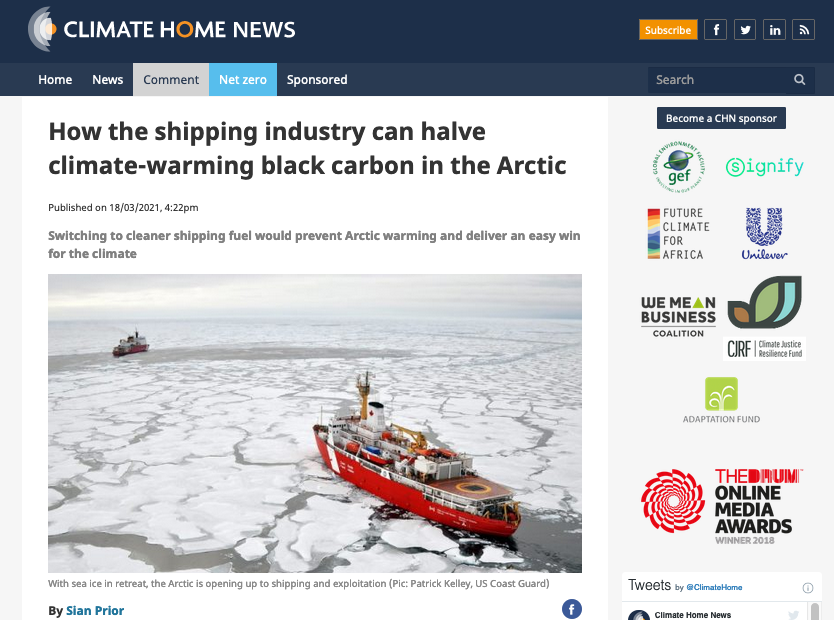

While most anthropogenic sources of black carbon pollution are being reduced in the Arctic, shipping emissions of black carbon have risen globally in the past decade, and in the Arctic by 85% between 2015 and 2019 alone. With climate warming driving the ongoing loss of multi-season Arctic sea ice, the region is opening up to more shipping traffic; with a five-fold increase is expected by 2050, we can expect that further increases in black carbon emissions from shipping will only further fuel an already accelerating feedback loop.

Around the world, ships typically burn the cheapest and dirtiest fuel left over from the oil refining process – heavy fuel oil (HFO), which produces high levels of black carbon when burned. About 7-21% of global shipping’s climate warming impacts can be attributed to black carbon – the remainder being CO2.

In November 2020, the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the UN body which governs shipping, approved a ban on the use and carriage of HFO in the Arctic – a ban that is set to be adopted this June. Although environmental and Indigenous groups fought for years for the Arctic to be free of HFO, the ban, set to be agreed in June 2021, contains serious loopholes, which, when implemented, will likely translate to minimal reductions in the use and carriage of HFO in 2024. Meanwhile, current growth in Arctic shipping is likely to lead to an increase in HFO use and carriage in the Arctic between now and mid-2024, when the ban takes effect and further growth by mid-2029, when the loopholes will finally be closed. Under this regime, black carbon emissions will, for now, continue to increase in the Arctic.

When the IMO’s Pollution Prevention and Response Sub-Committee meets on March 22nd for PPR 8, black carbon will be on the agenda. The IMO has been wrestling with what to do with regard to black carbon for over a decade now – but so far has taken no concrete action to reduce emissions.

During PPR8, IMO Member States have the chance to end this stasis. By putting in place regulations that cut emissions of black carbon from shipping the Arctic, the IMO can have a rapid and effective impact on black carbon emissions. The fix is simple – by moving the shipping industry to distillate fuels, such as diesel or marine gas oil (MGO), or other cleaner energy sources, for vessels operating in or near the Arctic, immediately reduce black carbon emissions in the Arctic by around an incredible 44%.

In addition, vessels using diesel or MGO should also be required to install and use particulate filters, as are already required by land-based transport.

Such a move could be led by industry, which would bolster confidence in the sector’s claims of recognition of its climate responsibilities, and is serious about staying the course towards eventual and inevitable decarbonisation. The bunkering industry, which supplies fuel for shipping, maintains that it has ample supplies of the necessary distillate fuels available in the Arctic to support a migration away from using heavy fuel oil. Ultimately, future international regulation will also be needed to eliminate all emissions of black carbon from shipping, as well as from other sources.

The Clean Arctic Alliance believes that by mandating a switch of fuels, the IMO – and the shipping sector could win an easy victory by achieving a major cut of black carbon emissions in the Arctic.t would also be a win for the global climate, for the Arctic and the people who depend on its ecosystem for their livelihoods.

Dr Sian Prior is Lead Advisor to the Clean Arctic Alliance, a 21-member coalition of non-for-profit organisations working to protect the Arctic region.

On March 22nd, the Clean Arctic Alliance will host a webinar: Switching Fuel – How to Cut Black Carbon Emissions from Arctic Shipping